There Are Lots of Ways to Get Started

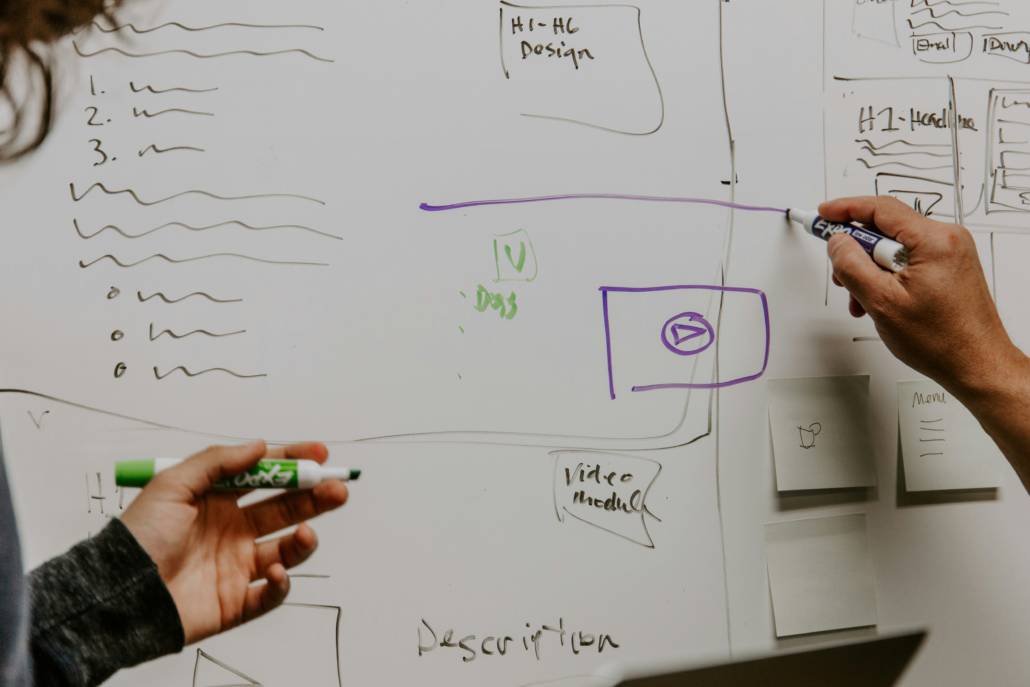

Over the years since I had my calling to do this work with families, I’ve sought out and even created peer groups where colleagues come together to discuss particular cases they’re involved with professionally.

The way that one family handles the work of transitioning their business or wealth to the next generation will differ markedly from the way another handles the process, for lots of good reasons.

As someone who advises families and helps guide the process, I can tell you that this is not something you can learn from a book.

When there’s a good deal of complexity involved with the family system and in the assets they want to transition, there are always a number of places you can begin, and figuring out where to start involves plenty of discernment.

Recognizing That It Will Evolve

One aspect of this work that can go unrecognized is that it can be very difficult to predict how things will actually unfold.

The technical part of wealth transitions, like the legal, financial, estate and tax planning and execution that more people are familiar with, can be comparatively straightforward, compared to the family and relationships part where I specialize.

Quite often much of the technical work will have been done before the family recognizes their need for some support in learning how to govern themselves together going forward.

It’s so important to get families started on discussions about this early on, while recognizing that a timeline and exact steps will be almost impossible to predict in advance.

See, for example, The Evolution of Family Governance.

Looking for Some Small Wins Early On

Back to the various peer groups in which friends and colleagues from various fields discuss real cases we’re dealing with, it’s always interesting to hear the variety of viewpoints, ideas, and tactics we suggest to each other.

One of the angles I typically come from is emphasizing the importance of moving slowly, so as not to “scare” the family too much, while also trying to make sure that we make some quick progress and get some small wins relatively early on.

This field continues to mature and many tools are available for us to put into our toolboxes, and being flexible is an important element when doing this work.

The discernment required to read the situation and figure out what should be done next is always part of wonderful discussions with colleagues.

See On Discernment and Resourcefulness for Family Clients

On Setting Expectations and Timeframes

Another aspect of family governance work that’s often underappreciated is how difficult it is to set a realistic timeline for the work.

This can become frustrating for practitioners early on as it’s always nice to promise the client family that the process won’t take too long.

I try to be extra careful in setting proper expectations whenever I begin working with a new family.

It is a process, and it will take time. And, trying to do it quickly can be a huge mistake.

The family needs to learn a lot and needs to become engaged in the process, and each family member has their own pace and ability for both of those.

My Favourite Arthur Ashe Quote

A couple of years ago in Starting a Family Council – Some Assembly Required, I shared some great yet simple wisdom that I like to remind myself, my clients, and my colleagues of, a quote attributed to Arthur Ashe:

“Start where you are.

Use what you have.

Do what you can.”

I’ve loved it since the first time I heard it, and it’s a great reminder when working with families.

In most cases the mere fact that you’re getting a family started is more important than exactly where you begin.

And of course at every juncture there needs to be a lot of thought and discussion around what comes next.

You can’t expect straight line progress either, as there are always some unexpected roadblocks and missteps along the way, which is par for the course.

More Art Than Science

Peer groups that include professionals who practice mostly in the structural content space are always interesting, because they often suggest great ideas, but may not appreciate the difficulty in executing them with a family.

This work is much more art than science.

I think of myself as a guide, helping the family make progress together, but where the pace of the work depends so much more on the family members than it does on me.